- Home

- Janine Cross

Shadowed By Wings Page 22

Shadowed By Wings Read online

Page 22

“I can’t return to Prelude,” I said in horror.

“You have no wish to do this for her? To learn who she was?”

“I can’t return,” I stammered.

“It’ll be for a short time only.”

“And if I don’t go?”

“Her history goes unrecorded and her name never joins those on the walls. You’ll never learn who she truly was, and her spirit will remain trapped here, as Prinrut, until you voice her free name and release her.”

“You do it. You go.”

“Think about it.”

“I can’t.”

“Oh, and Kabdekazonvia, inscribe her demise upon the walls, too. She was twenty-six years old.”

Lantern light and footsteps outside the door.

We both stilled, and the medic entered.

My blood rushed loud in my ears and I felt certain that he would know Misutvia and I had been talking, just by the guilty pounding of my heart. But after a cursory examination of my wounds, he merely turned to Misutvia and set her arm.

We didn’t have a chance to talk further, Misutvia and I, for as soon as the medic had set the broken bones, the plump eunuch came and fetched us both. I could scarce walk, so the eunuch pulled me along, my wrist held firmly in one of his paws. He murmured words he meant as encouragement.

“Just a little way to walk, Naji; not far and we’ll be at the stables. Not long now, not far. One more set of stairs and you’ll be there.”

It was day. Verdigris light filtered through the vine-choked casements we passed, and diurnal lizards skittered lightning quick along the stone walls. Outside, rain thundered down; the Wet had started in earnest. Rivulets of rainwater streamed in a ceaseless flow down the insides of the casements, splashing upon the invasive vines divaricating along the corridors, forming brackish pools on the corridor floor.

Obviously this shabby stone fortress had been built in slipshod haste, solely that the Ranreeb might learn the secret to breeding bulls in captivity. I felt an empathy for the stone edifice. Situated where it should not be, invaded and disfigured by aggressive, indifferent life, it was no different from my body. I didn’t hate the stone walls about me. No. I understood, only too well, that the enemy lay within the hearts of my jailers.

What I didn’t understand yet was that my enemy, too, lay within me. Within the complacency my fear had wrought.

If banished loneliness were to have a smell, if the promise of ecstasy were to be a scent, it would be that of venom.

As the citric tang of the dragons’ poison grew thick on the air, I knew we were near the stables. I stumbled, gasped, felt unbidden tears trickle down my cheeks. Despite my shattered physical and mental state, or perhaps because of it, I longed for the dragons’ embrace with a shuddering intensity. Without knowing from where the words sprang, I began muttering.

Embrace with thy obsidian-jeweled mouth, a creature made of blood coagulated. Embrace! and the honey light of wings ignited will teach that which they give not unto men.

The eunuch abruptly stopped. Annoyed by the pause, I looked from him to Misutvia. The eunuch wore a look of utter astonishment. Misutvia was an ocelot crouched in shadow, all dilated eyes, wariness, disciplined muscles poised to spring.

“What spoke you?” she whispered.

“The dragons are calling,” I answered, and I pulled the eunuch forward, toward the light.

The stables were steeped in venom, flagstone and flaxen chaff tacky with toxic mildew. Light blazed from sconces upon the venom-sweated walls, banishing shadow. Four stalls, four dragons. Four snouts huffed below eyes slant and amber and unblinking. Five daronpuis chanted stanzas while dashing oiled whisks over the heads of two women knelt in supplication. The daronpuis each chanted different stanzas, their murmured voices rolling and merging into one another like waves stirred from opposite shores of a lake.

I make thee mine own peer, reckless of what must come when thy luck must turn in the turning of time. My shame!

The words hissed from my mouth, as splendid and shocking as imported perfumes and pearls, ebony and coconuts, as threatening as the heaving seas upon which ships carried such varied treasure. The daronpuis shambled to an incredulous halt. The dragons’ eyes bored into me.

The dragons were bony with neglect, citrine scars where their wings had been amputated at birth running like accusing fingers along their flanks. Their dorsal ridges, briskets, and eye sockets protruded. Scales the dull green of desert cacti and the brown of dried blood hung as loose as rotting teeth upon wrinkled hides. The putrid stench of pressure sores on claw pads riddled the venom-rich air.

Words unreeled from my throat like kite silk lifted by wind.

I saw what I hoped never to see alive, the cur that fouled me pampered and well fed, the black snakes in plumes, the good yearning for death.

From where they knelt, beads of consecration oil dripping off their long, thin hair, Greatmother and Sutkabde stared at me, their pallid faces turning like orchids toward light.

“What blasphemy is this?” one of the daronpuis hissed. “Eunuch, control your charge! Is she mad? Make her kneel; how dare she foul the air with her voice.”

The eunuch shoved me forward, angry in his fright, and forced me to kneel alongside Greatmother and Sutkabde. Misutvia joined us, eyes hooded beneath her lowered lids.

“The effrontery!” another daronpu growled. “Is she like this always?”

I shuddered where I knelt, fearful, remembering the Retainers’ bunks, the ledger wherein the eunuch scribed marks against our names. What madness had gripped me to speak so?

“Holy guardians of Ranon ki Cinai,” the eunuch murmured, kowtowing to the daronpuis from where he stood behind my back. “She has never acted this way before.”

“It’s the venom,” one daronpu said, voice rich with certainty and not just a little smug with his own knowledge. “I’ve seen others react this way, from time to time. The Canon of Medicine recommends the juice of celery and honey, mixed with galangale and taken with the juice of a mouse ear, to remedy such venom fever. Failing that, tongue amputation, with white pepper applied thrice daily to the stump.”

Grunts from the gathered daronpuis.

“I’ll prepare the concoction at once, holy guardians,” the eunuch murmured. “I doubt she’ll require tongue amputation, though if necessary, I will not hesitate to do such. But you won’t give further trouble, will you, Naji?”

His corpulent form leaned over my shoulder and he pinched me, hard, in the small of my back.

“Forgive my impudence,” I mumbled, kowtowing.

More grunts from the daronpuis.

The eunuch departed. After several moments, the daronpuis resumed their circumambulation, fat-swollen cheeks pulping out holy stanzas. Splatter-splat went their whisks above my head, and their consecration oil stung the knuckle cuts on my cheeks. But I blinked away the pain and concentrated upon the immediate future, upon my expectation of venom’s burn.

As if sensing my impending descent into the toxin’s realm, the haunt trapped within me roiled like a maggot exposed to sunlight. My belly rippled beneath my bitoo much as a woman’s does when she is with child.

Shuddering, I awaited submersion, immersion, a merging with the divine.

FIFTEEN

Time passed in the viagand.

I experienced the madness and euphoria of dragonsong, was violated in the Retainers’ bunks, and “slept restlessly” with Misutvia, though our familiarities with each other were never as tender as what I’d experienced with Prinrut.

I babbled in the recovery chambers while greed-cruel daronpuis hung on my every word. I spoke of nests and good dragon fodder, bull hatchlings and well-groomed scales, intimating in my delirium that by improving the health of brooder dragons on all Clutches, a bull might hatch from an egg laid in captivity.

The daronpuis avidly recorded my words and I realized I’d struck gold. The imprisoned women, bayen all, knew nothing of the debilitating effects of hunger, knew

nothing of the needs of a dragon. Dream fevered, they all spouted politics, intimating in their interpretations of the dragons’ song how Temple might fortify its pillars and rid itself of destructive weeds.

I, on the other hand, spoke not of Temple or political stratagem, but of the dragons themselves. Of rich yolks produced only through the best fodder, of clean nests that a brooder might sit a clutch of eggs in comfort. I spoke of what I knew: how starvation and ill health reduced fertility.

For awhile, the novelty of my interpretations earned me much favoritism, so that my obligatory visit to the Retainers’ bunks prior to each visit to the stables was perfunctory, a brief sojourn where I was subjected to the crude ways of only one Retainer, he who by brawn and brain was deemed highest in the criminals’ rank.

During this time of favoritism, when my health was still somewhat with me and the promise of merging with the divine shone star bright before me, I found the strength of spirit to request a return to Prelude. During my brief, dark stay in that stinking sarcophagus, I released the spirits of Prinrut and Kabdekazonvia from imprisonment.

Prinrut, I learned, had come from Clutch Ka. Her name: Yimplar’s Limia. She’d been accused by her claimer of thrice provoking miscarriages of boy infants, and had been arrested for those heinous crimes. What little I knew of Prinrut, I was sure she’d not had the nature for such acts. She would have wanted a babe, certainly. The miscarriages had been natural and tragic. Her claimer had been impatient and influential enough to rid himself of her using Temple, and had probably assumed she would be made an onai, a holy woman serving in a Temple sanctuary for dying bulls. Or maybe he hadn’t cared what her future would be. Maybe he’d forgotten her the moment Temple had arrested her and his next claimed woman lay beneath him.

Kabdekazonvia had been arrested for recurrent insubordination toward her claimer, her kin, and Temple daronpuis. I could not reconcile the image of a defiant woman with that of sallow, gaunt Kabdekazonvia. Her apathy had been so complete. How could anyone who had once been so bold succumb to such lifeless submission?

I never thought to look at myself when I asked such a question.

When I’d completed Prinrut’s and Kabdekazonvia’s histories, meticulously carving the words into the damp wood with a stone, I whispered their names. I thought I felt Prinrut’s spirit enfold me briefly, tenderly, before dissipating beneath the crack under Prelude’s door. I imagined Prinrut taking flight as a trembling mist through stone corridors, to spiral out a vine-choked casement in a helix column. A Skykeeper appeared then, I was certain: It coalesced from the green jungle air, scooped the misty helix of Prinrut into its beak, and carried her to the One Dragon, safe in the Celestial Realm, where her life force was fed into its maw. Her essence combined with the Dragon’s and, fortified through recombination, the Dragon continued its eternal battle against evil.

Prinrut was free and whole.

Upon murmuring Kabdekazonvia’s name, I thought lights exploded about Prelude, white-orange sparks thrown from a temporal fire. Sharp and turbulent, the sparks zinged chaotically off Prelude’s walls, eventually discovering the crack under the door. Crackling and hissing like compressed bonfires, they disappeared from my sight.

This is what I thought I saw, and though I’ve never seen such since, I’m convinced that it was no hallucination evoked by the foamy residue of venom in my blood. No. I’m convinced that what I saw was the numinous release and regeneration of the essence of the women I’d known.

Understand, we didn’t lie with the dragons often. Such would have killed any woman, regardless of her tolerance for the dragons’ poison. Only thrice did I lie with the dragons during those long months in the viagand. Three times only. Yet how memorable they were.

What did I learn, during those pleated, undulating, wildly contracting and expanding days in the brooder stalls and the recovery berths? What did I hear?

Song that glorified and cleansed, melody that redeemed and transcended. Whispers melancholic and grief laden. I heard earth, heard water, saw fogged images of blood and radiance. I smelled loss and constraint, tasted barbarity and amputation. Rapture was a sound, had texture, knew grief.

Images sometimes flitted through the songs, fractured and blurred, seething, fuming, fermenting. Words belched from my mouth, disgorged by the tumult rampaging through me. Convulsive and savage, scorching and bestial, the images I saw and the eruption of words clashed and howled in orgiastic storm.

I felt my cloaca stretch as thin as fine paper as I laid an egg.

I flew from tree crown to tree crown, seeking my hatchling while the scent of humans burned like sulfur in my nostrils.

My hind legs trembled as, flanks heaving with exertion, I fought the young upstart that would mount my brooders.

But the images were not like this, not as I’ve presented them. They were frayed jigsaw pieces, worn at edge by time, and my intoxicated mind pieced them together as a confused whole, a collage that made little sense without the song and empathy that structured them. It was only during the dream-dizzy days and nights I slept in my burrow back in the viagand chambers that my mind assembled the pieces into coherent images, and in such assembling, many jigsaw pieces were lost, and pieces from the puzzle of my own life inserted instead for a logical picture to result.

Certain images did recur from each visit to the stables, though. Over and over, I experienced shinchiwouk as a bull. Over and over I felt territorial rage against my opponent, fought young bulls and old ones that I might prevail and mount the brooders gathered to watch. Long after I’d been returned to the viagand chambers, my limbs would twitch in a flashback of lunging, striking, turning, protecting flank and wing and throat. Over and over I triumphed, or was subdued and retreated.

And over and over, I felt the harrowing grief of losing a hatchling to python, vulture, or man. Over and over, I felt the agony of knife amputating wing from flank, felt hobbles about my forelegs, felt the burden of yoke across my shoulders.

But never once did I receive even an inkling as to why an egg laid in a Clutch was never an involucre for a bull dragon.

Never once.

My time of grace, if any stage of imprisonment can be deemed one of grace, was not long-lived.

After awhile, the uniqueness of my interpretations of the dragons’ music wore off and the daronpuis tired of my talk about fodder and brooder health. That, coupled with my increasingly irrational rambling while in the grips of venom’s embrace, only frustrated the daronpuis. Other strikes against me: my rapidly declining appetite; my disinterest in even pretending to create art, that I avoid sloth and animate my mind; the frequency of my “restless sleeps” in the viagand chambers, claimed against me by Greatmother and others as transgressions; my pallor and pustulant eyes; the frequency with which I wept for want of venom while in the presence of the eunuchs.

When Najiwaivia, One Hundred First Girl, arrived in the viagand chambers one afternoon, and shortly after, Najikazonvia and Najirutvia, I knew my time of favoritism was over. Those three would provide fresh interpretations of the canticles. My waning advantage was gone. Even in my debilitated, hazy state, I realized that my next obligatory visit to the Retainers’ bunks would go very hard indeed, and those unfathomable steel instruments in the recovery chambers would be employed by the daronpuis upon my person, that I might interpret the dragons’ song better.

I knew, then, that I’d become like Kabdekazonvia. I yielded to the knowledge as I yielded to everything else my jailers subjected me to.

I don’t know who said it first—Najiwaivia, if memory serves—but it roused us all from our individual stupors.

“Please forgive my insolence, Greatmother, but haven’t the eunuchs usually come by now?”

My lids rasped against my eyes like sacking as I blinked. Slowly, my gaze focused on Greatmother, who sat across from me on a cushion.

We had gathered, by rote, upon the cushions and divans in the central chamber for the morning feeding and were sitting there staring unblink

ingly inward. I’d had a poor night, as I oft did after a clawful of days had passed since my last union with a dragon and the venom in my blood was as cold and brittle as rime. My mother’s haunt had maggot-roiled within the cocoon in my psyche all night, clawing wildly at the membrane that enclosed it. Even in daylight as I sat with the rest of the viagand on the feeding cushions, waiting for the eunuchs to show up, I could feel the abhorrent squirming.

“She’s right,” another one of the new women murmured. “Haven’t the eunuchs usually come by now, Greatmother?”

Greatmother cocked her head to one side and stared hard at the jungle hues slipping through a casement.

“It would seem they are tardy today,” she eventually said in her measured, toneless voice. “I’m sure they have good reason.”

“How long do we sit here?”

“Until they come.”

“But we’ve been sitting for some time already. It’s past noon. I have need to relieve myself, Greatmother. Forgive me.”

We all looked at the light streaming through the casements, then, looked at the angle in which it fell as weak, wavering fingers upon floor and wall. I felt the merest nudge of surprise at noticing it was true: We’d sat there since dawn, and noon had come and gone. I also dully realized that I needed to visit the latrines.

Greatmother licked her chapped lips. “We must wait further.”

Silence. Beside me, Misutvia drew air into her lungs as though with great effort. “This hasn’t happened before, not since I’ve been here.”

We all looked at Greatmother, waiting for her to defend the eunuchs’ behavior or explain it by way of stating that such a thing had occurred before in her many years of imprisonment.

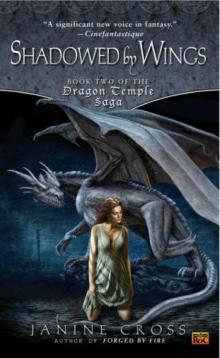

Shadowed By Wings

Shadowed By Wings